(Wang tiles foi proposto pelo matemático Hao Wang em 1961)

Assuma que teremos um conjunto de tiles onde cada lado está pintado de apenas uma cor. Por exemplo:

- Cada lado com uma cor.

- Dois lados com a mesma cor.

- Todos os lados com a mesma cor.

- Dois lados adjacentes com a mesma cor.

- Variação das cores já vistas só que em posições diferentes.

Por simplicidade mudaremos para duas cores apenas.

A ideia é reutilizar os mesmos tiles quantas vezes quisermos para botar eles lado a lado e formar um plano, porém com as cores laterais do tiles sempre casando. No exemplo seguinte temos 5 tiles e 2 exemplos de planos formados por eles:

Importante notar que:

- Tiles não podem se sobrepor.

- Tiles não podem ser rotacionados ou refletidos.

Pois não é possível saber se seriam tiles válidos sem conhecer a imagem utilizada neles.

Automation

Embora reutilização de tiles para gerar diversos planos/mapas não seja especial, Wang tiles adiciona a lógica de relacionar os tiles entre si. Isto nos permite verificar se um tile é válido numa determinada posição.

Por exemplo, possuindo 2 cores e 4 lados, podemos formar 16 (24) tiles diferentes:

Adicionamos um quadrado cinza no centro de cada tile.

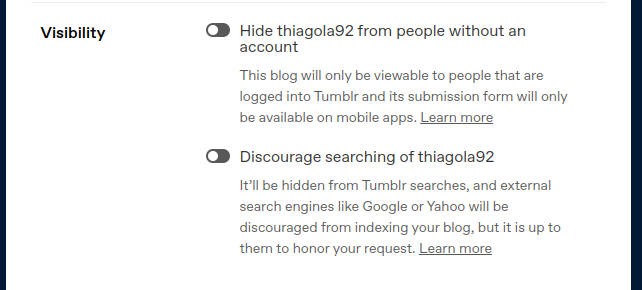

Botamos estes tiles na game engine Godot e nela definimos a relação entre os tiles.

Ao começar a pintar tiles dentro da game engine, podemos ver que ela consegue verificar qual tile é válido naquela posição ou se precisa alterar os vizinhos.

Em segundos conseguimos construir planos onde os tiles tem uma conexão entre si.

Variations

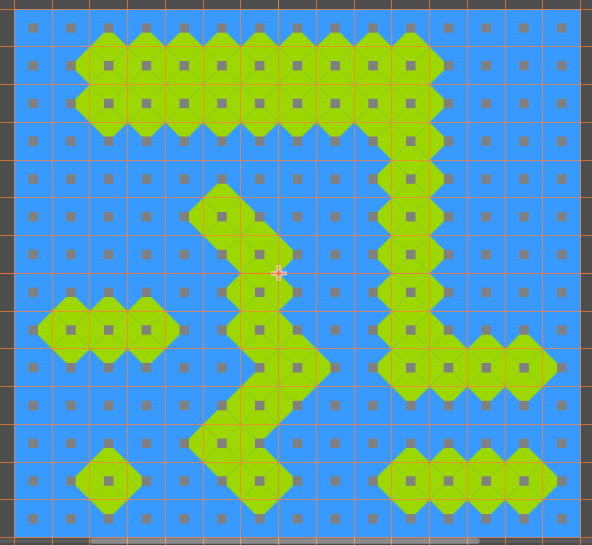

É importante notar que não há problema criar variações do mesmo tile. Por exemplo:

No momento de preencher por um tile válido naquela posição, a ferramenta iria ter que escolher entre 4 tiles diferentes. Algumas ferramentas como Godot escolheram aleatoriamente:

Antes

Depois

Rotation & Reflection

Na proposta de Wang não se pode rotacionar e refletir tiles pois não existe garantia que a imagem continuará fazendo sentido após rotacionada ou refletida.

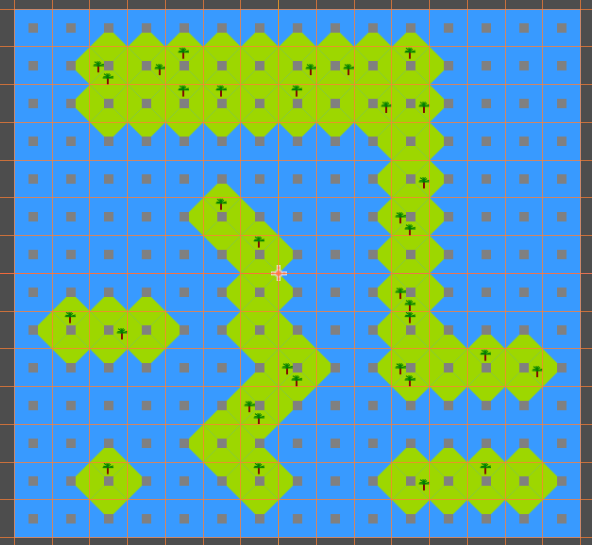

Porém como criador dos tiles, somos capazes de deduzir está informação e apenas fazer os tiles necessários. Vamos pegar este conjunto de tiles:

Alguns destes tiles são variações dos anteriores porém rotacionados ou refletidos. Levando isto em conta, podemos minimizar para 6 tiles apenas:

É importante notar que só é possível se conhecermos a imagem. Botando a mesma árvore utilizada anteriormente em um dos tiles, podemos ver o tile perder o sentido quando rotacionado mas não quando refletido:

Example

Todos nossos tiles tem sido com cores, porém as cores apenas servem para representar a relação entre os tiles.

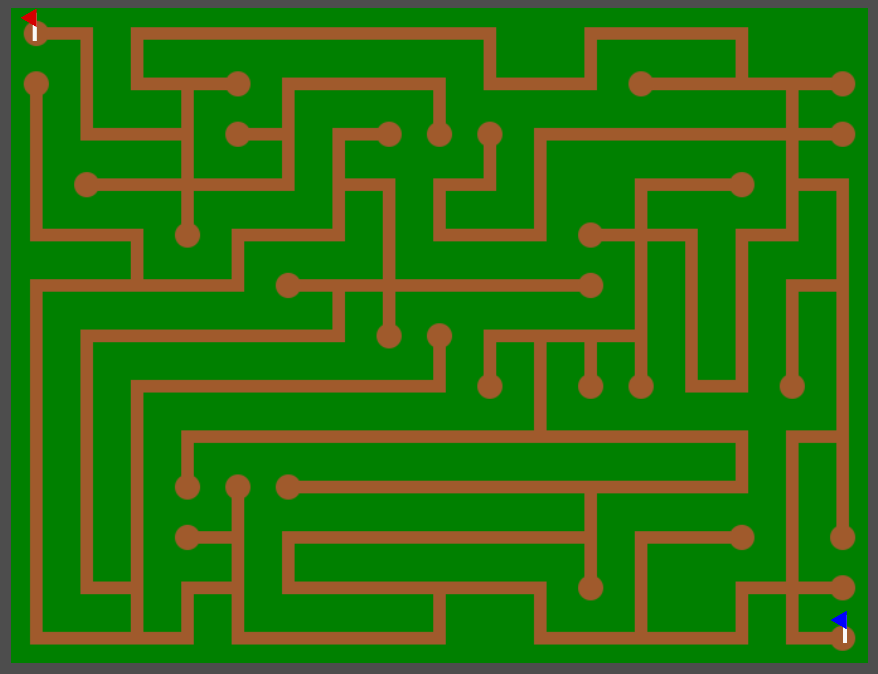

Para deixar isto claro, vamos substituir o desenho dos tiles por desenhos que melhor representem um labirinto. Vamos trocar azul por arbustos e verde por terra:

Utilizando estes tiles com suas rotações/relexões, podemos criar em segundos o nosso labirinto:

Este labirinto está com cara de circuitos da placa mãe. 🤔